Paving Euclid Ave

Duncan Virostko, Museum Assistant

“Several buggies and carriages were capsized… in attempting to “cross the waters” on Euclid St.”~Cleveland Leader, August 1855

When one travels down Euclid Avenue today, one does so on a modern asphalt and concrete surface. While not always smooth thanks to harsh Ohio winters, it is at least generally flat and dry. It has been this way for almost a century, a thoroughfare made for high speed automobile traffic that connects the East Side to Downtown Cleveland.

Early travelers of some two hundred years ago knew no such luxuries. They often sought and found relief from the wearisome experience of traveling over Euclid St. (as it was then called) at Dunham’s Tavern. The story of how that street came to be paved is one of a changing neighborhood and rapidly improving transportation technology.

A stage coach makes it’s way up the unpaved Euclid St., aka Buffalo Road, from Public Square. (Lithograph, Thomas Whelpley, American, 1834).

At first, Euclid Street was unpaved, a simple dirt track through the wilderness likely carved by indigenous peoples and wildlife over hundreds of years. It ran alongside an east-west ridge parallel to Lake Erie, which at its highest lay 100ft above sea level. This would attract wealthy residents to build their homes directly on top of the ridge, with homes with large front yards that separated them from the road, partly for reasons which will become apparent shortly. Early settlers however were much more pragmatic, and sited their homes as near to the street as possible.

In the dry months of the year, the road suffered from the ruts made by passing wagons and stagecoaches. Striking a rut in the wrong place could easily break a wheel, which might halt one’s journey for some time while a skilled wheelwright was found to repair it. Wagon and coach wheels were a marvel of 19th century engineering, but they were not interchangeable like modern cars. The heavily rutted and ungraded road would have made the journey from Buffalo to Cleveland a slow, and bumpy affair, to say nothing of the dust.

In the wetter months of the spring and fall, an ungraded dirt road becomes an impassable quagmire. Stagecoaches that became stuck in thick mud often required the passengers to get out and push them free. Thus, if you traveled by coach in the spring or fall, you paid extra fare to walk!

These road conditions were as appalling as they were common, which is why in spite of them the Ohio General Assembly declared Euclid St. a public highway in 1832. As a link to Buffalo, the road was invaluable to commerce. It is likely not a coincidence that Rufus Dunham decided to open his tavern in 1833, adding an addition to his home not long after acquiring his license. With the official declaration, which made the new highway a “post road” for carrying mail to Buffalo, Rufus must have realized that stagecoach traffic would soon be increasing, and that they would need a place to “water the horses and whiskey the men.”

In 1837, the first major work on Euclid Ave was done: the first half mile east of Public Square was graded to make it "passable and easy for ascent and descent.” This work was followed up on in 1838, when twelve foot wide sidewalks and a culvert were laid to “drain the water complained of from the south side.” The culvert proved somewhat ineffective, and between 1839 and 1840 a gutter was built to drain run off into it.

Thus, even from its earliest days, Euclid became infamous for its poor drainage. It was a running joke that it doubled as the city’s “frog pond.” In the early 1840s, fruit and ornamental trees were planted along the street in an attempt to address the issue, but to no avail. In 1853, The Daily True Democrat criticized the city government for not properly addressing the problem, saying “ the city fathers intend taking a sail on one of the many lakes on Euclid Street.” In August of 1855, a letter to the editor of the Cleveland Leader complained that “Euclid Street is worse than a mud hole—it is a lake—an inland sea. The whole thing is a credit to our city government.”

The complaints about issues of drainage came in spite of major improvements to Euclid that happened throughout the 1850s.

John Loudon McAdam, ca. 1830 (National Gallery, London)

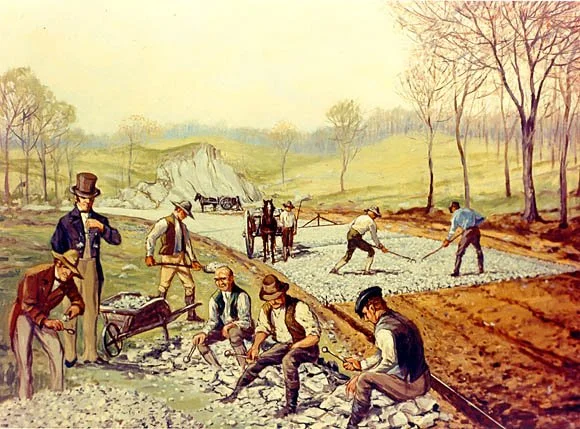

In the early United States, there were many different ways to pave roads. The superior, but more expensive way was with Macadam. Named for its Scottish innovator John Loudon McAdam, this is what we today would simply call a gravel road: MacAdam’s principle innovation was specifying a uniform size of gravel, and shaping the cross section of the road such that it had a significant hump so as to allow for rain to runoff into drainage ditches on the other side of the road. In order to “macadamize” a road, gravel would have to be painstakingly broken down by hand using small hammers until it was no larger than ¾ inches in diameter. The purpose of this exacting sizing was to allow the gravel to settle, after traffic had driven on it, into a solid surface with each stone fitting tightly against one another. The result was a smooth, durable road surface that was largely self-healing and had excellent drainage. The first of many roads built to this design in the United States was the Boonesborough Turnpike, running between Boonesborough and Hagerstown Maryland in 1823.

Macadamizing the Boonesborough Road, the first of it’s kind in the United States, 1823.

With the advent of motor vehicles, at first steam and later electric and gasoline powered, macadamized roads began to suffer damage. Deep ruts in the roads were cut by fast moving narrow wheels, making them impassible. The solution was found to be creating a matrix of tar and crushed stone, creating the “Tar Macadam” or Tarmac we know today. This type of road was first tried experimentally in 1871 in Cleveland in Public Square, and must have been at least somewhat successful as the following year the city bought it’s first steamroller the following year.

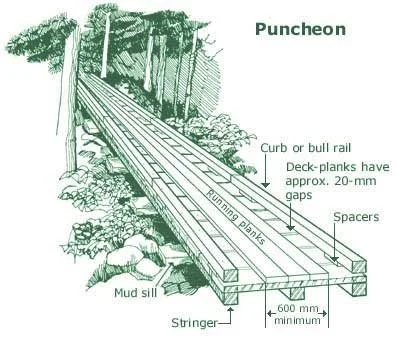

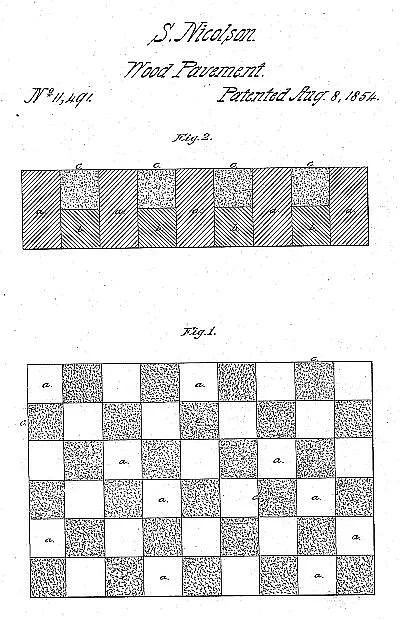

The builders of Euclid St. opted for a second, very popular and economical, but perhaps less successful technique of paving roads: building a plank road. As shown in the diagram below, the plank road is merely a road whose pavement is made out of wooden beams and planks, like the floor of a house. From 1844-1854 the United States underwent a “plank road boom”. The chief promoter of this kind of road, George Geddes, based on his experience in Canada, argued: “Over that part of the road in Toronto, that wore out in eight years... It is found that the cost of repairs on a McAdam [macadam] road is easily greater than upon a plank road- without taking into account the great difference in the first cost. The McAdam road out from Toronto cost four hundred dollars every year to keep a mile in order... if the [plank] road is constructed, the repairs will be trifling until the road is worn out .” . He also calculated that the yearly cost of maintaining a Mcadam road would be sufficient to re-plank a worn out plank road three times over. Thus, the Plank road seemed to offer a cheap way to greatly improve the speed and comfort of roads

The reality, as Cleveland’s experience would prove, was slightly less rosy. One and a half miles of Euclid east of Cleveland was planked in 1848, at the height of the “boom”. However, merely planking did not improve the road as flooding persisted, causing the wooden boards that made up the surface of the road to warp. The result was a road just as bumpy as it had been before.

This was much the experience of Mark Twain who, upon being asked how he liked his trip over a plank road between Kalamazoo and Grand Rapids Michigan declared "It would have been good if some unconscionable scoundrel had not now and then dropped a plank across it."

During the Plank Road boom of the 1840s, many roads in the US were planked by private companies funded by citizens to pave the road. This ad from May 1849 is typical of the “Plank Road Boom” period.

In 1852, the original planking in the road was replaced with puncheons, or half logs, with the greater thickness hoped to resist this warping. The 1852 road stretched even farther east than the 1848 road, running three miles from Public Square to what is now East 55th St.

In 1857, public outcry over the state of Euclid forced a dramatic change to the streetscape. The two miles between Public Square and what is now 40th St. were re-planked, at last given proper sewers, and for the first time lighted with gas streetlights. The work took until 1859 to complete, likely because it was funded almost entirely by the local property owners along Euclid rather than by the city government. In 1860, the street was then widened from 30ft to 41ft to accommodate the increasing traffic in the growing city.

Yet planking was still proving inadequate as a road surface. By 1863, another effort to repave the street, this time between Public Square and what is now East 21st Street was launched. This time, the favored paving solution was another technique entirely, albeit one that still used wood.

The specific type of pavement settled on by the road builders in 1863 was the newly patented Nicholson Pavement. This featured coal tar soaked blocks of wood, which were less prone to rotting. Patented Aug 8th, 1854 by Samuel Nicholson, this was the most popular form of woodblock pavement in the 19th century. As the process for creating it was still under patent, the builders had to obtain local rights from the American Nicholson Pavement Co. . This company was later subject to a Supreme Court Case, City of Elizabeth v. American Nicholson Pavement Co. , which ruled that although public use of an invention a year before a patent application usually made the invention ineligible for a patent, this did not apply to cases where the invention was being used by the public for testing purposes. Samuel Nicholson’s laying of a test stretch of pavement along a turnpike to allow the public to test it was ruled not be the sort of use which would otherwise bar him from patenting the process, on the basis there was no other practical way to test a paving technique.

Wood block paving was a typical technique at the time, often used in the paving of industrial buildings thanks to its low price and great durability. Wood block paving offered a flatter surface than cobblestone paving, at lower cost, and the wood supposedly dampened the sound of horses hooves striking the pavement. Still, it was often very slippery when wet or frozen over, and being wood which floated was often lifted by flooding.

Today, wood block paving is seeing a resurgence, in such applications as walkways and patios. The production of concrete produces 8% of the present man-made CO2 emissions, contributing significantly to global climate change. It also causes excessive run off. Wood block paving uses a carbon neutral material and is permeable, thus reducing the environmental impact of paving a low traffic area.

By 1870, Cleveland could boast of having some 9 miles of Nicholson pavement roads, and 10 miles of stone paved roads. Today, Cleveland is also home to one of the last Nicholson Pavement roads in the United States: Hessler Court. The road was originally the private drive of Emery M. Hessler. It was originally paved with tarred Norfolk Pine blocks, and was ceded to the city in 1908 for use as a public street. Nestled in the University Circle neighborhood, the street connects with Bellflower Road, and the surviving brick paved street Hessler Road. From 1969 until 2019, the area hosted a local arts & music festival, the Hessler Street Fair.

New sidewalk, curbs, subgrade, & Black Locust woodblock paving were installed along Hessler Court by the City of Cleveland.

In 2024, the City of Cleveland executed a major restoration of Hessler Court, repairing the road’s subgrade, curbs, and sidewalk as well as replacing the wood block pavers. The project took two month, and cost $700,000. The blocks had previously been replaced in the 1980s. The latest blocks on Hessler Court are made of Black Locust. This is a type of tree which Dunham Tavern to this day still has growing on its grounds. Black Locust is one of the hardest native woods in North America, and was frequently grown in the 19th century as a source of firewood, as it burned with less ash than other species of wood. Being a harder wood than pine, it should have a longer lifespan. Thus, Hessler Court has a bright future as Cleveland’s only remaining wooden road.

In 1873, the wood block paving was replaced with brown sandstone, quarried from Medina, Ohio, along the three miles between Public Square and East 55th St., and the street widened to 60 ft. At last the Avenue was beginning to take form, as one of the most prestigious roads in the city.

Although the issues of drainage seemed to never have quite been alleviated, by the 1870s the streetscape of Euclid Ave was largely one of a refined city avenue, whereas a few decades earlier it had been little more than a rough country road. This was both a reflection and a cause of the increasing prosperity of the neighborhood forming around the street.

When Rufus Dunham operated his Tavern, from 1833 to 1853, the road had still been largely unpaved. Indeed it seems that it was not paved beyond East 55th St until the late 1800s. No doubt the difficult road conditions which in times of rain rendered the road nearly impassable were a benefit to Dunham’s Tavern, which offered the weary traveler a place to stay and wait for the frog pond to dry up.

New palatial mansions, such as that of Dunham neighbor S.V. Harkness, demanded paved roads to match! From the 1880s onward the bulk of Euclid Ave. was paved in stone and brick.

Yet these kinds of conditions were intolerable to the new class of people who were settling along Euclid Ave after the Civil War: there was little point in owning a massive, luxurious suburban villa if it was difficult to get to from the city and its looks were spoiled by the muddy road running past it. Thus, early migrants to what would become Millionaire's Row invested their hard earned money into making massive improvements to the streetscape, which in turn made the locale a more fashionable and desirable place to live. Thus, improvements to Euclid St. not only paralleled the development of paving technology in the 19th century, but drove a demographic shift in the area that changed the character of the area it ran through.

Thus by the 1880s, streets in Cleveland began to look more modern. Some 2.2 miles of street had an asphalt surface, and 1.2 miles were Tarmac. Brick roads, which would continue to be popular for many years to come, were first introduced to Cleveland in 1888 with the paving of Carroll & East 89th (then Bolton). Although at the time secondary streets were still largely unpaved, and new paving projects were progressing at the snail-like pace of 1 new mile per year, the rise of the automobile in the decades afterwards would quickly ensure that all future roads were paved in one way or another.

Today, we still complain about the bad roads in Cleveland. Yet, even the worst paved roads of today however would have seemed a luxury to 19th century Clevelanders. They had to contend with a Euclid Avenue that was unpaved and seemingly always swamped. Throughout the 19th century, various new technologies were used to help improve road conditions along Euclid Ave. The street evolved slowly, from an unpaved road into a plank road, then later into a wood block paved road. Eventually, wooden pavers gave way to stone and brick, until these were superseded after the turn of the century the widespread use of concrete and the addition of tar to the Macadam road construction technique created surfaces better suited to the newly developed automobile. The rapid evolution of Euclid Ave. from an early highway for commerce into a residential boulevard was a reflection of the changing demographics of those who lived in the neighborhoods along the road. Some of Cleveland’s wealthiest families, prospering after the Civil War from the rapid growth of industry in the United States, sought not just to construct the mansions for which “Millionaires’ Row” would become best known for, but also to improve the street they were situated on, and raised the money to do so. Still, there were persistent issues with the paving and drainage of the street which led to the spectacle of muddy roads fronting opulent homes. It would take them until almost the end of the “Millionaires’ Row” period to fully solve their road problems and beautify the street.

Wood block pavers at Cleveland Foundation’s HQ at 6601 Euclid Ave.

Nowadays, the times of plank roads and wood block paving are long behind us. Only historic oddities like Hessler Court remain as proof that there were once alternatives to the present day techniques of paving. Yet, while our roads are smoother and more durable than any 19th century pavement could ever hope to be, they are still bad—but in ways that 19th century people could not have imagined. The concrete used to pave not just roads, but walkways, patios, and other surfaces, is a significant contributor to the warming of Earth through greenhouse gases that is causing a catastrophic change in climate. When one combines its contribution to global C02 emissions of 3% with the 11% caused by road transport which would not be possible without its use, and also consider the other environmental impacts such as excessive runoff, it is clear that alternative pavement solutions are needed. Fortunately, the past is showing the way to the future in this regard. Wood block, stone, brick, and other carbon neutral and permeable pavement options lower the environmental impact of new paving projects, whilst still providing safe surfaces for low traffic applications.

Dunham Tavern Museum & Gardens has worked closely with the Cleveland Water District to create a permeable paver surface for our parking lot, and our close neighbors the Cleveland Foundation have paved one of their patios using wood block pavers. Hopefully, these new applications of once forgotten technologies will pave the way to a cleaner and better method of paving in general, one which will relegate pollution creating concrete to use for only the highest traffic roads such as Euclid Ave and ultimately help to preserve the natural environment for generations to come.

Sources:

Cigliano, Jan Showplace of America: Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue, 1850-1910. Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio, 1991. Ch. I: “From Buffalo Stage Road to Village “Frog Pond,” 1816-1860.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plank_Road_Boom

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicolson_pavement

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macadam

https://case.edu/ech/articles/h/hessler-rd-and-hessler-court-historic-district

https://psci.princeton.edu/tips/2020/11/3/cement-and-concrete-the-environmental-impact

https://blog.apis-cor.com/the-effects-of-cement-and-global-warming

https://case.edu/ech/articles/s/streets

https://www.cleveland19.com/2024/09/05/brick-by-brick-historic-neighborhood-rebuilds-its-legacy/