Dunhamsburgh, Pt. II

The Neighbors of Loretta J. Dunham-Pier

Duncan A. Virostko, Museum Assistant

This article is Part II of a series on Dunhamsburgh, the neighborhood between East 63rd St and East 69th Street, along Euclid Ave. The moniker was one promoted by Rufus Dunham, because this stretch contained Dunham Tavern, his second home to which he retired and was later owned by his youngest daughter Caroline, and the home of his eldest daughter Loretta. Read Part I here: https://www.dunhamtavern.org/blog-3-1/the-four-doctors. ~ Editor

Loretta J. Dunham-Pier’s home, along the northern side of Euclid Ave, Ca. 1881.

By the 1880s, the area once known as Dunhamsburgh had undergone rapid development. No longer a charmingly rural roadside stop, it was now part of the fashionable “Millionaires Row” neighborhood along Euclid Avenue. Yet, the Dunham family was still an important part of the community. Although the Dunham’s Tavern had gone out of business in 1853, being sold to its second owner George Williams and Rufus Dunham had died in 1862, the Dunham family continued to live in and be a part of the community he had founded. Loretta J. Duham-Pier, and younger sister Caroline S. Dunham-Welch would continue to live in the area. Caroline inherited her father’s new home on the west side of the Tavern, and Loretta continued to live in her own home between East 63rd and East 65th Streets, at the time known as Kennsington and Dorchester Streets respectively, and Euclid Avenue.

Across the street from Loretta’s modest home were the massive new mansions of two Cleveland business magnates: Stephen V. Harkness and Alva Bradley.

The mansion of Stephen V. Harkness, on the southern side of Eulcid Ave, across the street from Loretta J. Dunham-Pier’s home, Ca. 1881.

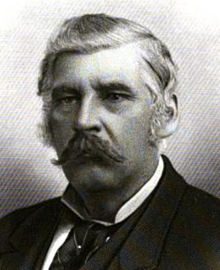

Stephen V. Harkness

Stephen V. Harkness was born in 1818, in Fayette, New York. His mother Martha died when he was age two, and his father David M. Harkness moved the family to the Western Reserve shortly thereafter. Young Stephen began his climb to the very top of 19th century society humbly, beginning work as an apprentice harnessmaker at age 15. In 1839, his apprenticeship ended, and Harkness moved to Bellevue, Ohio. Being a simple harnessmaker however was not enough for Harkness, and he soon became involved in a variety of different business ventures. By 1855 he had moved to Monroeville, Ohio, and opened a brewery and became a leading local businessman. By 1860 he had become involved in banking, and his fortunes began to rise exponentially. In 1864, amidst the turmoil of the Civil War, Harkness financed William Halsey Doan’s latest venture to supply crude oil to refineries during the very first “oil boom” in the United States. The deal quickly made both men fabulously rich, and by 1866 Harkness retired from business and moved to Cleveland. Although Harkness no longer needed an income to support himself.

Yet, he continued to be involved in the early oil industry, primarily as an investor. He began this second life in 1867 by pledging $60,000 (roughly $1.2 million in today's terms) to the Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler Co. Henry Flagler, the eponymous partner in the new company, was the step-brother of Harkness, being born to their step-mother during her second marriage. Later, Stephen Harkness would be the second largest stockholder in, and serve as the director of, the firm’s successor: The Standard Oil Co.

Standard Oil Co. Articles of Incorporation signed by Stephen V. Harkness, ca. 1870.

Harkness’ wealth was tied to the earliest oil booms. These were driven by the rapidly increasing demand for petroleum as a source of fuel for oil lamps. Confederate raiders during the Civil War directly attacked the Atlantic and Pacific whaling fleets that previously provided whale oil for lighting. Attacks on shipping also drove up the cost of insuring merchant ships, depressing maritime trade generally. The result was a decline in the US whaling industry and a pressing need for an alternative and superior replacement for whale oil.

Kerosene, a refined petroleum product, was that solution, and oil fields in Ohio and Pennsylvania were able to develop new technology to take advantage of it. Gasoline was at the time considered a worthless byproduct of refining, and it would not be until the early 20th century that it came to be used as fuel for newly invented automobiles and motorcycles. In the meantime, however, the vast majority of American homes were lit using kerosene lamps, especially rural homes, some of which would not be electrified until the 1930s. And that market was more than enough to make owners of oil companies disproportionately wealthy.

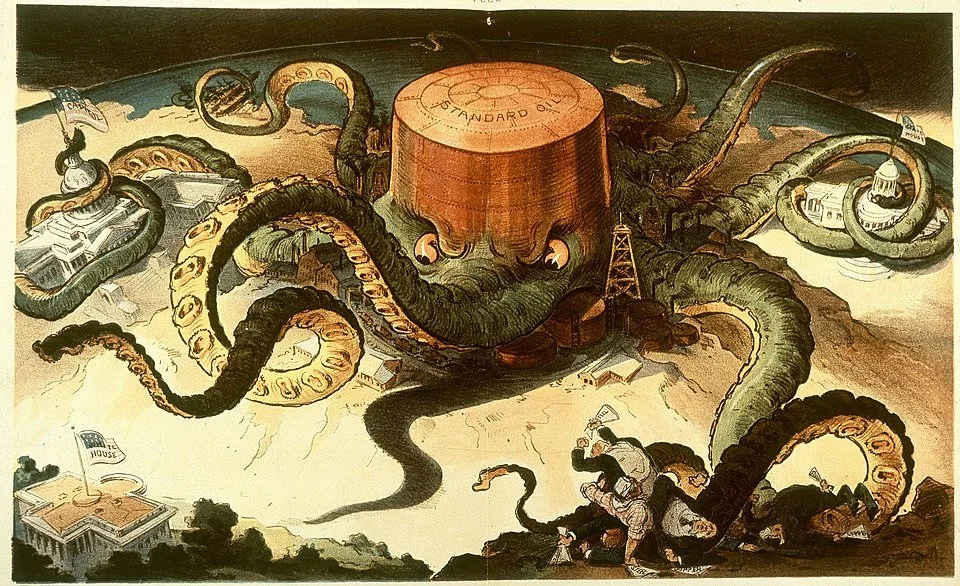

Political cartoon, depicting the Standard Oil Co. monopoly as an octopus, ca. 1904.

The dark side of that wealth is well known, but nonetheless bears repeating.

Standard Oil was one of the first vertical monopolies in the United States, being able to control the extraction, refinement, shipping, storage and sale of their product completely via unfair business practices. Standard Oil’s monopoly, over which Harkness as the company’s director presided, was so complete and egregious that it inspired some of the first anti-monopoly laws and lawsuits in US history. Ultimately, the company’s monopoly was broken up, and it was forced to either sell or spin off its various subsidiaries. This led to the creation of SOHIO, The Standard Oil Company of Ohio. SOHIO long outlived the original version of the company, surviving until sold to British Petroleum in 1987. The oil industry in the United States was largely born in Ohio and Pennsylvania, and delivered by businessmen like Rockefeller and Harkness. However, as the case of Standard Oil shows, it was conceived in sin… being based on unfair business practices which caused widespread economic harm, long before the environmental harm it caused was well understood.

Medallion of Stephen V. Harkness, Euclid Ave facade of The Arcade, ca. 1930.

Harkness left a major impact on the architecture of Cleveland, thanks to his vast wealth. Stephen Harkness was one of the major supporters of the construction of The Arcade in 1890, alongside other notables such as John D. Rockefeller, Marcus Hanna, and Charles F. Brush. The building was designed based on the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II built in 1861 in Milan, Italy, and was designed by Cleveland architects John Eisenmann and George H. Smith in the Richarsonesque style. In commemoration of his support for its construction, a bronze medallion with Harkness’ likeness now adorns the Euclid Avenue entrance to The Arcade, part of a renovation of that facade dating to the 1930s and executed by famous Cleveland architecture firm Walker & Weeks. Stephen V. Harkness would ultimately die in 1888, one of the richest men then alive, on board his private yacht.

Harkness Tower, Yale University

Anna M. Harkness, his second wife, however, rather outdid him in terms of architectural legacy and philanthropy. Married to 32 year old Harkness when she was only 16, on February 13, 1854, Anna’s life was marked with tragedy as three of her four children predeceased her. Her first daughter, Jennie A. Harkness was born in 1856 and only lived until age 8. Her second daughter, Florence, was born in 1864 the same year as her sister’s death. In 1895, she married Louis H Severance of Severance Hall Fame. Unfortunately, she only enjoyed a few months of marriage before dying of septicemia. Anna then used the considerable wealth of her late husband to construct the Florence Harkness Memorial Chapel at Case Western Reserve.The neo-gothic chapel was originally intended for female students to study the bible but now acts as an musical performance space for the college, and features beautiful original stained glass windows from Louis Tiffany & Co. When her son Charles, born in 1860, was struck down along with his wife by the beginnings of the terrible flu epidemic in 1916, she then donated $3 million to Yale University, his alma mater, for the construction of the Harkness Quad. This included the Harkness Tower, a massive stone structure also in the Gothic Style and was designed by James Gamble Rogers, a Yale classmate of her surviving son Edward S. Harkness.

Alva Bradley, ca. 1883.

Alva Bradley in contrast was an important figure in Great Lakes shipping, and was a classic 19th century self-made man. He was born November 27th, 1814 to father Leonard and mother Roxanne Thrall Bradley, in Ellington, Conn. Alva would subsequently move in 1823, to Brownhelm, Ohio. At age 19 he left home to become a sailor on the Great Lakes, sailing aboard the 50 ton schooner Liberty. Much of his early career was aboard the 15-ton Olive Branch, a small ship that served ports in the Lake Erie Islands. By 1839, he had risen to Captain of the 47-ton schooner Commodore Lawrence. Two years later he would join his business partner Ahira Cobb of Vermillion, Ohio to construct the 103 ton South America, for the princely sum of $3,200. He would sail her until 1852, when he married his wife Helen M. Burgess of Milan, Ohio and in 1853 would alongside Cobb found the Bradley & Cobb shipyard in Vermillion.

In 1859, Bradley had decided to move to Cleveland, and bought out Cobb’s share in the company. By 1868, he had decided to transfer his shipyard and other business interests to Cleveland. His yard in Cleveland would build 18 vessels between 1868 and 1882, at the rate of about a ship a year. These were constructed entirely for the use of his own new fleet, the Bradley Transportation Company. Massive for the time when ships owners and operators were often one and the same with their Captains, Bradley’s fleet cornered the market on iron ore shipments coming from Superior, Wisconsin and was able to set the standard shipping rate. Bradley would go on to found the Cleveland Vessel Owners’ Association in 1880, that would later become the nucleus of the Lake Carriers’ Association, the professional organization of Great Lakes shipping that continues to operate and be based in Cleveland even today.

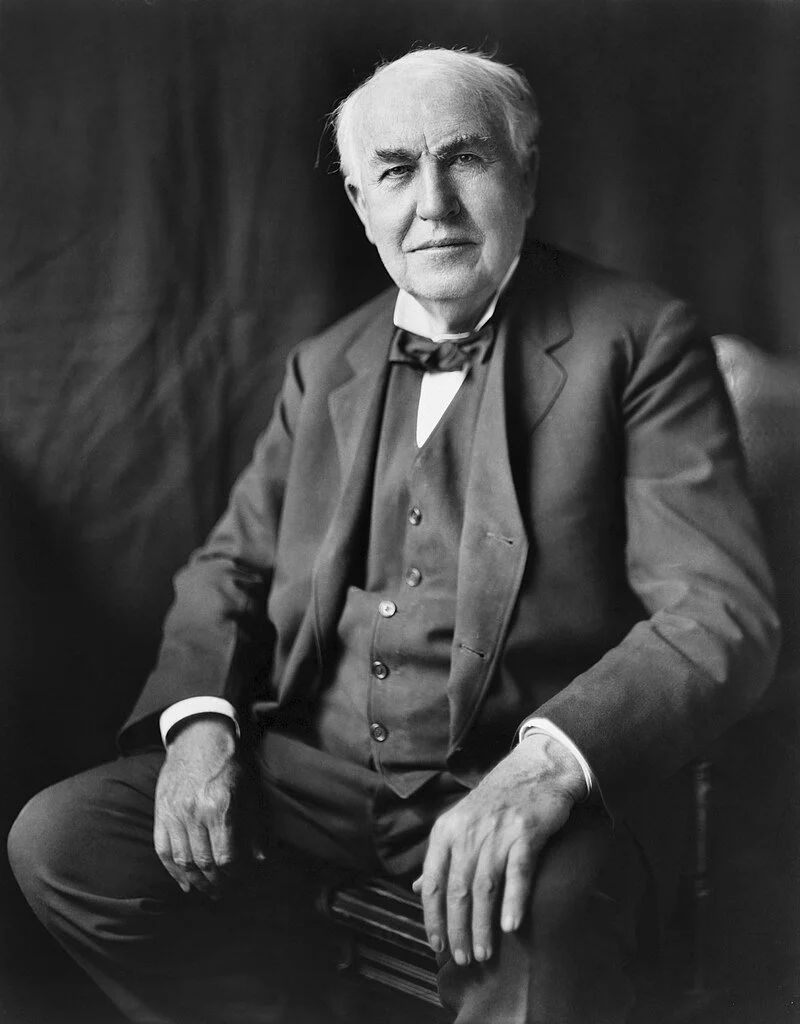

Thomas Alva Edison, named for Alva Bradley, ca. 1922

If Alva Bradley’s first name seems familiar to readers, it is likely because of Thomas Alva Edison. The unusual middle name of the famous inventor is no coincidence: he shared the name with Bradley because his parents were good friends with the Captain and named their son in tribute to him.

Bradley also left a significant architectural legacy in Cleveland, although unlike Harkness he did not live to see its completion. In 1883, he hired Cleveland architectural firm Cudell-Richardson to design a new office building for his shipping firms and his grandson, Alva Bradley II’s real-estate businesses, on West 6th Street in the Warehouse District.

The firm designed a building in its signature style, Richardson Romanesque. This architectural style was the hallmark of American architect Henry Hobson Richardson, and made use of the new materials of iron columns to radically change the shape of large commercial buildings. The style is particularly associated with Chicago, influencing an entire generation of architects there to develop their own variation, the so-called Chicago school. The most notable element of the style are large multi story arches over top of large bays of windows, which make the facade of a commercial building like the Bradley seem both lighter than previous styles and also more unified. Using newly developed iron columns allowed for the construction of these large arches, as well as making the buildings more fireproof: an important consideration in an era when smoking was common, commerce was conducted with reames of paper, and most buildings, even those in brick or stone, had wooden support members. A single ember from a cigar could erase an entire business empire overnight!

Considered a mid-rise building today, the Bradley Building was in its time massive, soaring to eight stories, or 128 ft, above Cleveland in a time when a building half its height would have been considered tall. Made of red brick, and featuring iron columns, it was to an extent a modern marvel. Yet, it was also a transitional building, still featuring wooden beams because steel structural members were not yet common and brittle cast iron tended to fail when used in beams. It was also pushing the envelope on masonry construction: future high-rise buildings would be made of concrete and steel instead of brick and iron. Completed in 1886, the Bradley Building was thus a transitional moment in American architecture. Unfortunately, the elder Alva Bradley would not live to see it, dying in 1885.

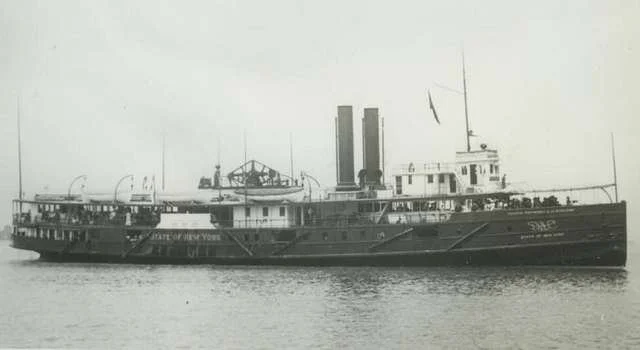

The PS. State of New York, launched as the PS. City of Mackinac for the Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company, owned by Alva Bradley II. His grandfather Alva Bradley I would have been alive to see her launch in 1883.

The ship served the D&C from 1883 until 1892, then was sold to competitor C&B but later briefly rejoined the D&C fleet from 1911-1918. She later served as the Columbia Yacht Club of Chicago’s clubhouse until 1983, with her remains not scrapped until 2007. This made her the longest serving and last surviving D&C ship.

His grandson, also Alva Bradley, would continue to use the building for many years, and it served as the offices of the famous Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company which ran passenger steamships between the namesake cities and other locations until it’s bankruptcy in the late 1920s due to the rise of automobiles. The building would then go on to be used by the Cleveland garment industry, which was centered in the Warehouse District. By 1979, the building had been converted into studios and apartments for a burgeoning artist community.

Unfortunately the building's owners at the time, Trisket Realty, had slated the aging building for demolition, citing increasing heating, cooling, and maintenance costs. They declared the venerable building an “uneconomical investment”, and informed the tenants of their intentions. Fortunately for Cleveland’s architectural history, however, they had not reckoned with the artists’ determination and ability to organize. Swiftly, a tenants’ union was formed with the intention of purchasing the building and preserving it. The building was soon listed on the National Register of Historic Places, over the objections of the owners.

Owners of buildings objecting to such a listing is quite common and seems to be born partly from a misunderstanding of the purpose of the Register itself. Contrary to popular belief, the Register does not actually afford any protection from demolition in and of itself. Instead, the Register is an important piece of documentation which can be used to gain historic tax credits: credits which would in fact be available to owners were they to apply for them.

It was those same tax credits which helped the tenants organization to extensively restore the Bradley building, after they raised sufficient funds to purchase the building itself in 1984. Today, it stands as a shining example of creative reuse and mixed use buildings, and was the first project of its kind east of Chicago.

Loretta J. Dunham-Pier’s neighbors in Dunhamsburgh were representative of the growing wealth of the city of Cleveland, which was slowly transforming Euclid Road into “Millionaire’s Row”. Although their grand houses are long since demolished, both left architectural legacies in Cleveland. Yet, the two men who lived across the street on Euclid Avenue could not be more dissimilar when it came to how they acquired and used their wealth. Both came from humble backgrounds: one a harness maker, and the other a sailor. Stephen V. Harkness, however, was a businessman at heart and tried many different lines of work before finally striking it rich in the first American oil boom of the mid to late 19th century. Alva Bradley, by contrast, continuously worked in largely the same line of business, slowly gaining experience and prestige as he moved from sailor to captain to shipyard owner and fleet owner. Harkness used his wealth largely to reinvest in the oil business, being a controlling interest in the newly formed Standard Oil Company, which used unfair business practices to create a vertical monopoly which drove competitors out of business and inflated prices. That the Harkness family name is connected with charity has more to do with his second wife Anna M. Harkness’ terrible personal losses of her children to disease, which took the lives of wealthy and poor alike in the 19th century. The contrast between Anna and Stephen is particularly apparent in their architectural legacies: Stephen Harkness was a key financier of the Arcade in Cleveland, progenitor of the modern shopping mall, whereas Anna Harkness’ most significant contribution to architecture is the Harkness Tower at Yale University. Similar to Stephen Harkness, Alva Bradley’s lasting contribution to Cleveland architecture was commercial in nature. The Bradley building was a triumph of new architectural materials pushing the limits of building in the late 19th century, yet Alva did not live to appreciate his legacy. Instead the building served mainly his grandson, named in his honor, until economic conditions and age demoted it to a prosaic purpose as a garment factory. It is ironic, then, that an artists collective should have made it into their home, and subsequently showed the power of tenants unions, historical preservation tax credits, and adaptive reuse to revitalize depressed areas. Perhaps the contrast between how Alva and his grandson of the same name earned and spent their money is more poignant: Alva was a sailor who spent his time and money on things directly related to that line of work, such as forming a professional organization for it. In contrast, his grandson was a real estate broker, who was also a long time owner of the baseball team then known as the Cleveland Indians. In some ways, the elder Bradley’s life might be read as a cautionary tale, since he devoted his life to his work, when perhaps he might have spent his time and money elsewhere. Yet, unlike his grandson, his work was far less exploitative and when he spent his fortune it was for the good of his industry rather than mere personal amusement. In the span of two generations, the Bradley family had gone from being of modest means to one of the richest in the country. Yet, with wealth came new social responsibilities, some of which they and other contemporaries like the Harkness’ were not equal to. They thus were ultimately typical of the shift between 19th and 20th century society in the United States, as society transformed from one with a high degree of social mobility and a developing economy, to one with a fully developed capitalist system with entrenched generational wealth and low social mobility. Loretta J. Duham-Pier and her neighbors navigated this social shift, some with more deftness than others, as they lived together in the Dunhamsburgh neighborhood during the 1880 and 1890s.

Sources

Stephen V. Harkness

https://case.edu/ech/articles/h/harkness-stephen-v

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_V._Harkness

https://case.edu/artsci/music/about/facilities/florence-harkness-memorial-chapel

Alva Bradley

https://case.edu/ech/articles/b/bradley-alva

https://sanduskyhistory.blogspot.com/2017/03/captain-alva-bradley.html

https://thebradleycle.com/about/history/

https://clevelandmagazine.com/cleader/biz-hall/inductees/Details/alva-bradley/

https://case.edu/ech/articles/b/bradley-transportation

https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/electronic-records/rg-079/NPS_OH/80002978.pdf